1. Introduction

2. Swedish Experimental Data for Blast-induced Damage

3. Numerical Model

3.1 Material Model

3.2 Numerical Model Verification

3.3 Numerical Simulation of Coupled Single-hole Blasting

4. Results and Discussion

4.1 Fracture Zone Prediction

4.2 Wave Attenuation

5. Conclusions

1. Introduction

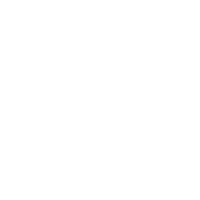

Rock blasting is often used to excavate hard rock because of its cost-effectiveness. During the drilling and blasting operations, the detonation of a blast hole generates high gas pressure and shock waves. Part of the energy from the explosion is used in the process of crushing and breaking the rock, resulting in the formation of a crushed zone and fracture zone surrounding the blast hole (Li et al., 2021a), as shown in Fig. 1. Controlled blasting is used to reduce the damage to the excavation boundaries since any damage beyond the excavation line requires an extra support system to maintain safety (Sim et al., 2017). Accurate assessment of blast-induced damage is important during the construction phase. It depends on blast hole diameter, rock mass properties, and the amount of explosive used (Dey & Murthy, 2012). A recent study indicates that the crushed zone extends around 3-5 times the radius of the blast hole, while the fracture zone spans roughly 10-15 times the radius of the blast hole (Lu et al., 2011).

Many researchers presented theoretical models based on the pressure to estimate fracture zone radius from blasting (Mosinets & Gorbacheva, 1972; Xahykaeb, 1974; Senuk, 1979; Xu & Liu, 1995; Hustrulid, 1999; Sim et al., 2017). Pressure is a crucial measure used to determine damage. Rock fails in the form of a fracture zone around the blast hole when the tensile stress exceeds the dynamic tensile strength of the rock. Unfortunately, information on pressure factors and dynamic tensile strength of rock is not easily accessible.

In recent times, dynamic numerical simulations have been a popular tool used to simulate blast fracturing (Yi et al., 2018; Jeong et al., 2020; Bird et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023). Nevertheless, numerical modeling has a drawback due to its limited accessibility to engineers due to the complex theoretical foundation and programming prerequisites. An alternative approach involves using simple empirical equations derived from extensive datasets, which engineers may readily use. Swedish experimental data is collected to estimate the fracture zone, and its equation is used. Numerical simulations then validate the predictability of the fracture zone. A finite element model using LS-DYNA has been developed to analyze the fracture zone resulting from single-hole blasting. The numerical model is validated by small-scale laboratory experiments. The results of numerical simulations are compared with Swedish experimental data. The statistical analysis of experimental data results in a linear equation. The empirical equation may be used to determine the extent of the fracture zone resulting from blasting, providing useful guidance for the blast design.

2. Swedish Experimental Data for Blast-induced Damage

In Sweden, extensive research has been conducted by Swedish Rock Engineering Research (SveBeFo) from 1990 to 2003 to estimate blast-induced damage in underground blasting in hard rock formations. The primary objective of this study was to quantify and minimize the extent of the damage zone and to enhance the standards for perimeter blasting in tunneling. Smooth blasting technique was employed for perimeter blasting. Explosives often used for these types of operations are normally quantified on their linear charge concentration, measured in kg/m. Different sizes of blast holes but commonly utilized for smooth blasting were used, and the blast-induced fractures were identified by slicing the remaining rock into parts and using penetrants to make the fractures visible, as shown in Fig. 2. Next, crack length, crack number, and pattern were examined.

Data is collected from seven different sources, namely (Langefors, 1958; Sjoberg, 1979; Pusch & Stanfors, 1992; Ouchterlony, 1997; Sjoberg et al., 1997; AnlaggningsAMA 1999; Ouchterlony et al., 2009). Fig. 3 Shows all the collected data on a log-log scale.

3. Numerical Model

3.1 Material Model

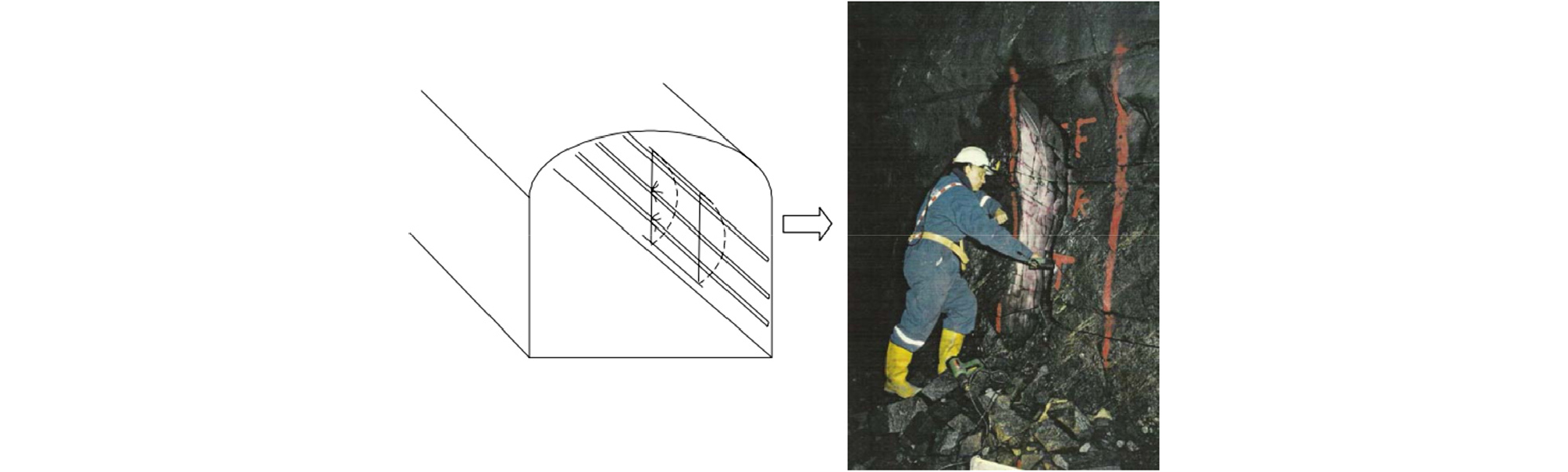

3.1.1 RHT Material Model for Rock

LS-DYNA offers a variety of rock material damage models, such as Cowper-Symonds, Continuous Surface Cap model (CSCM), Karagozian-Case model, Holmquist-Johnson-Cook (HJC) model, and Riedel-Hiermaier-Thoma (RHT) model. These models are utilized to replicate cracks in rocks caused by compression, tension, and the reflection of tensile stress. However, each model has limitations and is unsuitable for all simulation scenarios. Recent studies have utilized HJC and RHT models. The HJC model is only capable of compression damage and is not able to simulate tensile damage (Wang et al., 2021). However, the RHT model can simulate both compression and tensile damage as it considers strain hardening, damage softening, confining pressure, and strain rate. It uses the Mie-Gruneisen form to depict pressure change, using a relationship between p-α compaction and a polynomial Hugoniot curve proposed by (Borrvall & Riedel, 2011). Fig. 4(a) shows a diagram of the p-α equation of state (EOS). It has three stress limit surfaces, which consist of an initial elastic yield surface, a failure surface, and a residual friction surface to calculate material strength. An illustration of a typical loading scenario can be illustrated in Fig. 4(b).

The failure surface (σf) represents the maximum deformation stress a material can endure. It is represented as

where fc is the compressive strength, σf* is the normalized strength relative to compressive strength, p* is the normalized pressure, Fr is the dynamic strain rate increase factor, εp is the plastic strain rate, R3 is used to characterize the factor’s decreased strength on the shear and tensile axes, and ϴ is the Lode angle.

According to experimental investigations (Hao & Hao, 2013), the dynamic strength of the rock increases as the strain rate increases. Zhang & Zhao (2014) compiled results from several studies on the strength of rocks at various strain rates. The dynamic increase factor (DIF) for the strain rate of rock material during compression and tension is shown in Eq. (2) and Eq. (3), respectively.

where Frc(εp) and Frt(εp) are the strain rate increase factors under compression and tension, respectively. εp is the strain rate. Under blast loading, the compression strain rate is approximately 103 to 105 s-1 (Li et al., 2021a). Barre granite rock could be subject to strain rates of up to 1000 s-1 or more (Gharehdash et al., 2020). Using Equation 2, the dynamic increase factor is 5.12. Granite has a uniaxial compressive strength of 167.8 MPa, and the dynamic compressive strength is approximately 864 MPa.

Equation 4 provides the formula for deriving the initial elastic surface from the failure surface by applying the elastic strength parameter.

where σel is the initial elastic surface, Fe is the elastic strength parameter, and Fc is the cap function.

Once the rock’s hardening state approaches the maximum strength on the failure surface, any more inelastic loading will result in damage accumulation, which is regulated by plastic strain. The following equation provides the plastic strain at failure.

The variable D represents the extent of damage (0 ≤ D ≤ 1.0) before fracture begins (D=0) and after damage begins to accumulate (D > 0). When (D=1), the material is completely damaged. Δεp represents the total plastic strain, whereas εpfailure represents the plastic strain at which failure occurs and is expressed as:

where pt* is the normalized failure cutoff pressure and εf,min is the minimum allowable plastic strain. D1 = 0.04 and D2 = 1 are the constants. The RHT model parameters for granite rock are taken from (Xie et al., 2017) and shown in Table 1, while the values for sandstone are taken from (Li et al., 2021b) and displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The RHT parameters for rocks (Xie et al., 2017; Li et al., 2021b)

3.1.2 Blast Loading and Equation of State

The blast load is modeled using the material model of explosive with Jones-Wilkins-Lee (JWL) EOS to describe the relationship between the pressure and volume caused by the detonation, which is described as follows.

where Pd is the explosive pressure, V is the relative volume of the explosive product, E is the energy per unit volume of the detonation product, and A1, B1, R1, R2, and ω are the constants. The parameters for PETN emulsion explosives are selected from (Banadaki & Mohanty, 2012) and shown in Table 2. At the same time, parameters for ANFO explosives are taken from (Sanchidrian et al., 2015) and listed in Table 3.

Table 2.

Parameters for PETN explosive and JWL EOS. (Banadaki & Mohanty, 2012)

| Density (kg/m3) | VOD (m/s) | PCJ (GPa) | AJWL (GPa) | BJWL (GPa) | R1 | R>2> | ω | E0 (GPa) |

| 1320 | 6690 | 16 | 586 | 21.6 | 5.81 | 1.77 | 0.282 | 7.38 |

Table 3.

Parameters for ANFO explosive and JWL EOS. (Sanchidrian et al., 2015)

| Density (kg/m3) | VOD (m/s) | PCJ (GPa) | AJWL (GPa) | BJWL (GPa) | R1 | R2 | ω | E0 (GPa) |

| 830 | 3230 | 2.21 | 216 | 1.84 | 7.16 | 0.87 | 0.34 | 1.56 |

3.2 Numerical Model Verification

To simulate accurate blast detonation and rock fracturing, the numerical model is compared with a small-scale physical test conducted by (Banadaki & Mohanty, 2012) in the laboratory. The investigations documented both the rock fracture pattern and the attenuation of pressure. The sample consists of five different material types: PETN, polyethylene, air, copper, and rock. A cylindrical rock sample of Barre granite with a diameter of 144 mm and a height of 150 mm was used for the test. A 6.45 mm borehole diameter was drilled in the center of the sample along its axis. A copper sheet with 0.6 mm wall thickness was used in the borehole wall to prevent the entering of explosive gases into the cracks. Polyethylene sheath was used to cover the strands of PETN. Its outer diameter was 2.5 mm, and air was used as a coupling medium. The outer diameter of the air was 5.25 mm.

The polyethylene, air, and copper parameters are provided in Tables 4, 5, and 6, respectively (Li et al., 2021a). Null model and Gruneisen EOS are used to simulate polyethylene, the null model and linear polynomial EOS to model air, and the johnson cook model and Gruneisen EOS are used for copper.

Table 4.

Parameters for polyethylene and Gruneisen EOS. (Li et al., 2021a)

| Density (kg/m3) | C | S1 | S2 | S3 | g | V0 |

| 915 | 2901 | 1.481 | 0 | 0 | 1.64 | 1 |

Table 5.

Parameters for air and polynomial EOS. (Li et al., 2021a)

| Density (kg/m3) | C0 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | E0 (J.m-3) | V0 |

| 1.29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 250000 | 1 |

Table 6.

Parameters for copper and Gruneisen EOS. (Li et al., 2021a)

In this study, a model with the same dimensions was constructed to verify the RHT model by comparing the fracture pattern and pressure attenuation predicted in the experiment, as shown in Fig. 5. To improve the computational efficiency, a plane strain model was developed. Fixed constraints were imposed in the thickness direction to create a quasi-two-dimensional model. This analysis uses a hexahedron solid element with a uniform mesh size of 0.1 mm. The whole model consists of 3267,428 elements.

During the blasting, a large deformation occurs. Hence, convergence and computational efficiency are crucial. For this purpose, The Arbitrary Lagrange Euler method is used to address this issue. The explosive, polyethylene, and air are modeled as Euler parts, while copper and rock are modeled as Lagrange parts. The element formulation of 11 was assigned to the Euler part, and the element formulation of the Lagrange part was set to 1. The outer surface boundaries were left free to resemble with the experimental sample. The total duration was set to 30 µs. As a final step, the LS-DYNA solver is implemented. Table 7 shows the card options of LS-DYNA used in this study.

Table 7.

LS-DYNA cards used in this study

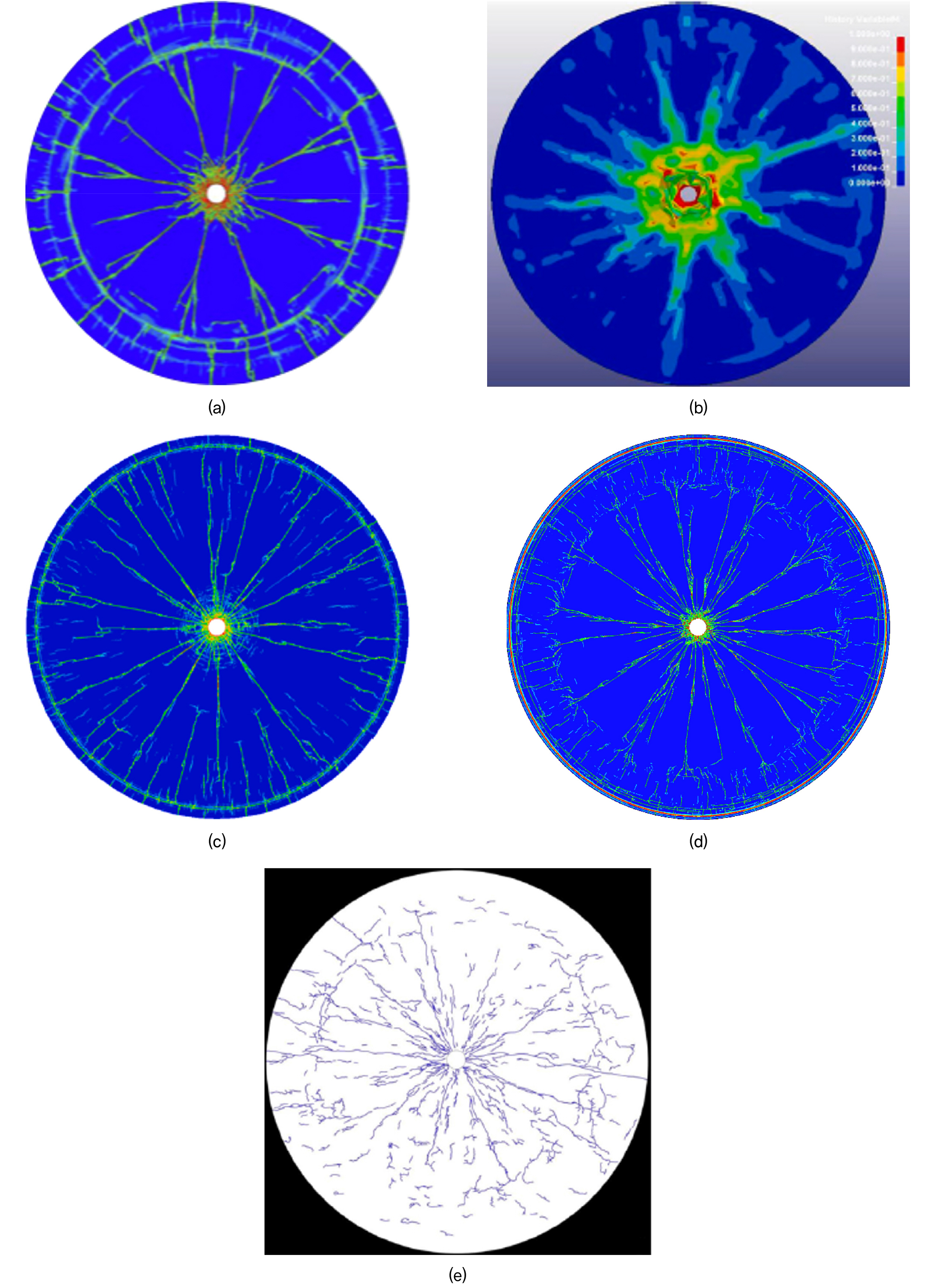

Plastic deformation occurs around a borehole in the radial direction when an explosive detonates. A crushed zone is formed as stresses around the borehole are higher than the compressive strength of the rock, as shown in Fig. 6(a). With distance shock waves decaying into stress waves, in this region, the tensile strength of the rock is less than the stresses around it, thus creating a fracture zone, as shown in Fig. 6(b). As the wave propagates through the rock medium, it reaches the free surface and is reflected as a tensile wave, resulting in spalling, as shown in Fig. 6(c). In this region, the tensile strength of the rock is less than that of the tensile stress wave, and circumferential tensile cracks also develop, as shown in Fig. 6(d). Based on the above results, the damage zone of the rock can be divided into three parts: the crushed zone around the blast hole, the cracked zone, and the region between circumferential cracks and the free surface.

Fig. 7. Shows the comparison between the findings of this study and previous numerical and experimental investigations. All the numerical simulations used the RHT model. Fig. 7(a) demonstrates that the numerical model accurately forecasts all three zones, but Fig. 7(b) only shows crushed and fractured zones. Furthermore, Fig. 7(c) does not accurately predict the occurrence of circumferential fractures. Fig. 7(d) in this work effectively forecasts and displays a comparable pattern to the experimental findings, with the exception of spalling occurring in close proximity to the free surface.

Fig. 7

Comparison of numerical results with experimental and previous numerical results (a) RHT model (Xie et al., 2017), (b) RHT model (Jayasinghe et al., 2019), (c) RHT model (Li et al., 2021a), (d) RHT model (This study), (e) experimental result (Banadaki & Mohanty, 2012)

To further validate, this study focuses on investigating stress wave attenuation. Four pressure gauges were arranged in an experimental investigation, with readings set at 11, 22, 29, and 40 mm. The maximum pressure derived from numerical analysis at various distances is compared to the experimental data using a log-log scale. Fig. 8 demonstrates a close correspondence between the numerical findings and the experimental results. This model is further used to simulate the process of coupled single-hole blasting in the following section.

3.3 Numerical Simulation of Coupled Single-hole Blasting

In this section, a numerical model of coupled single-hole blasts is investigated. The dimensions of the model were set to 10 m × 10 m × 0.05 m (width × height × depth), as shown in Fig. 9. Non-reflecting boundary is applied to the outer edges of the finite element model to eliminate the influence of reflected stress waves. The displacements in the depth direction were constrained due to the significantly smaller size of the model in this dimension compared to the other dimensions.

Mesh size has a significant effect on wave propagation and the ultimate magnitude of fractures. The selection of the optimal mesh size involves considering six different kinds of mesh sizes. 50, 25, 20, 15, 10, and 5 mm are used in this investigation. Fig. 10 shows the time history of pressure for sandstone at a distance of 2.5 m. The pressure peak seen in the 50 mm mesh is notably lower than that observed in the 5 mm mesh. Similarly, Fig. 11 illustrates a significant and abrupt alteration in the pattern of fractures, reducing from 50 to 5 mm. The 50 mm mesh reveals the presence of four radial fractures, but the 5 mm mesh exhibits a greater number of radial cracks. Therefore, a 5 mm mesh was used for this investigation. The model has meshed into 1882,923 solid elements.

Two specific kinds of rocks, granite and sandstone, are being investigated. The characteristics and properties of these rocks are presented in Table 1, respectively. Two kinds of explosives, PETN and ANFO, are used. The properties of these explosives are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The fracture zone produced is examined using ten different charge diameters ranging from 17 to 100 mm. A total of 40 parametric analyses are carried out. Tunneling operations typically use small to medium charge diameters, but larger ones are often employed for mining. Linear charge concentration is often utilised in tunneling operations for perimeter blasting. It is used to quantify the entire quantity of explosives used in 1 meter of a loaded blast hole and is given in kg/m. The calculation may be determined using the following equation.

where L is linear charge concentration in kg/m, d is the blast hole diameter in m, and re is explosive density in kg/m3.

One important assumption in this study is that damage along the axis of the borehole is assumed to be uniform as the radial damage. If the blast hole depth of 1 m is developed with a uniform mesh, the total elements will be approximately over 35 million, which will consume more time. Hence, the borehole depth was selected as 0.05m.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1 Fracture Zone Prediction

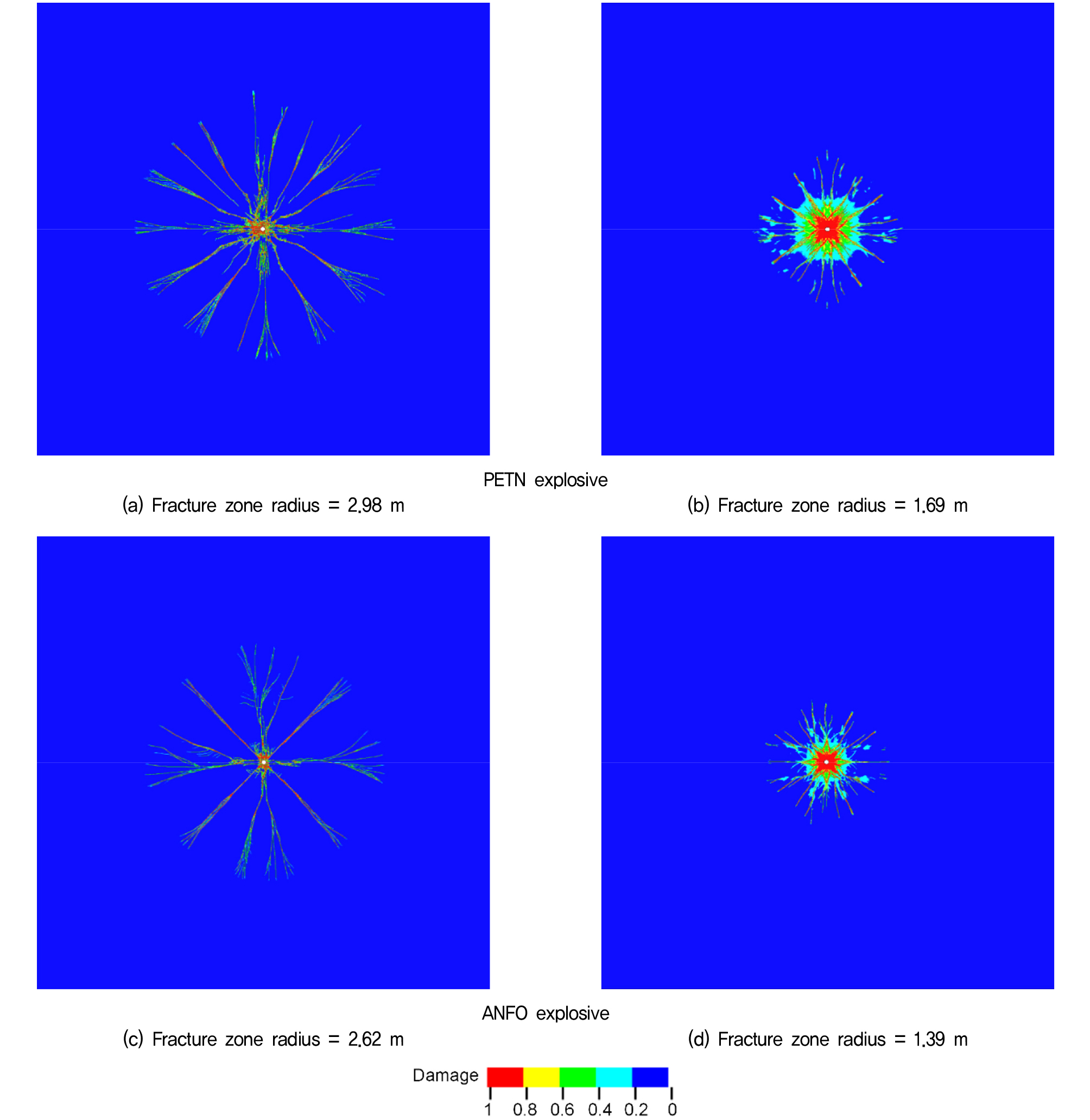

Parametric analysis is conducted on granite and sandstone with two types of explosives. Ten types of borehole diameters are used, ranging from 17 to 100 mm. Linear charge concentration is calculated for every borehole. Table 8 shows the fracture zone predicted from PETN explosives for two types of rocks. A small-diameter borehole results in a small fracture zone, while a large-diameter borehole results in a large fracture zone. Granite rock has a larger fracture zone than sandstone, as granite’s compressive strength is higher than sandstone. The granite fracture zone ranges from 2.24 to 2.98 m, while sandstone ranges from 1.26 to 1.69 m. Table 9 shows the fracture zone predicted from ANFO explosives for two types of rocks. The granite fracture zone ranges from 1.66 to 2.62 m, while sandstone ranges from 1.02 to 1.39 m.

Table 8.

Predicted fractured zone radius for PETN explosive

Table 9.

Predicted fractured zone radius for ANFO explosive

Fig. 12 shows the fracture zone obtained from a 42 mm blast hole. For PETN explosives, Fig. 12(a) shows that the fracture zone for granite is 2.68 m. crushed zone is small because of the high compressive strength of the granite, while long fractures can be seen. Fig. 12(b) shows that the fracture zone for sandstone is 1.54 m. A crushed zone is formed around the blast hole, followed by fractures. Fig. 12(c) and (d) show fracture zones of 2.48 and 1.2 m for granite and sandstone, respectively. As seen, ANFO explosives have a smaller fracture zone than PETN explosives. Similarly, the fracture zone for a 100 mm blast hole is shown in Fig. 13. Compared to a 42 mm blast hole, it shows a larger fracture zone. Granite rock shows a small crushed zone around the borehole, with large radial fractures. Sandstone shows an obvious crushed zone with small fractures.

Based on these investigations, it is clear that the blast hole, rock type, and explosive type influence the radius of the fracture zone. A smaller blast hole will result in a smaller area of damage, while a larger blast hole will cause a greater damage zone. The number of fracture zones in hard rock will be higher than in soft rock. Hard rock has a little crushed zone, but soft rock displays a noticeable crushed zone. High-density explosives generate significant pressure, resulting in extensive damage, while low-density explosives create less damage.

Fig. 14 displays a numerical prediction of the fracture zone, which is then compared to the experimental data set. For granite rock with PETN explosive, a 17 mm blast hole has a charge weight of 0.299 kg/m, which is calculated using equation 8, resulting in a 2.24 m fracture zone radius. ANFO explosive has 0.188 kg/m for the same blast hole, resulting in a 1.66 m fracture zone radius. When the density of the explosive is changed, the charge weight will also be changed, and the fracture zone for the same rock will be different. For a 100 mm blast hole, a fracture zone of 2.98 m is predicted for PETN explosives with a charge weight of 10.36 kg/m. Meanwhile, a 2.62 m fracture zone for the ANFO explosive is predicted to have a charge weight of 6.51 kg/m. Similarly, 17 mm and 100 mm blast holes with PETN explosives for sandstone rock will result in 1.26 m and 1.69 m, respectively. The fracture zone predicted for ANFO explosives for sandstone is 1.02 and 1.39 m, respectively. By applying statistical analysis to experimental data, three distinct confidence levels may be forecasted. The predicted fracture zones for both small and large borehole diameters fall outside the established confidence level. However, the fracture zones for medium blast holes, often used in tunneling, align with the range of experimental data. Fig. 15 displays the range of borehole sizes within the confidence level for granite rock (38 to 64 mm) and sandstone (25 to 51 mm).

The following expressions can be used to express the confidence level of 5, 50, and 90%.

5% confidence level:

where fr is the fracture zone radius in m, and L is linear charge concentration in kg/m.

50% confidence level:

95% confidence level:

4.2 Wave Attenuation

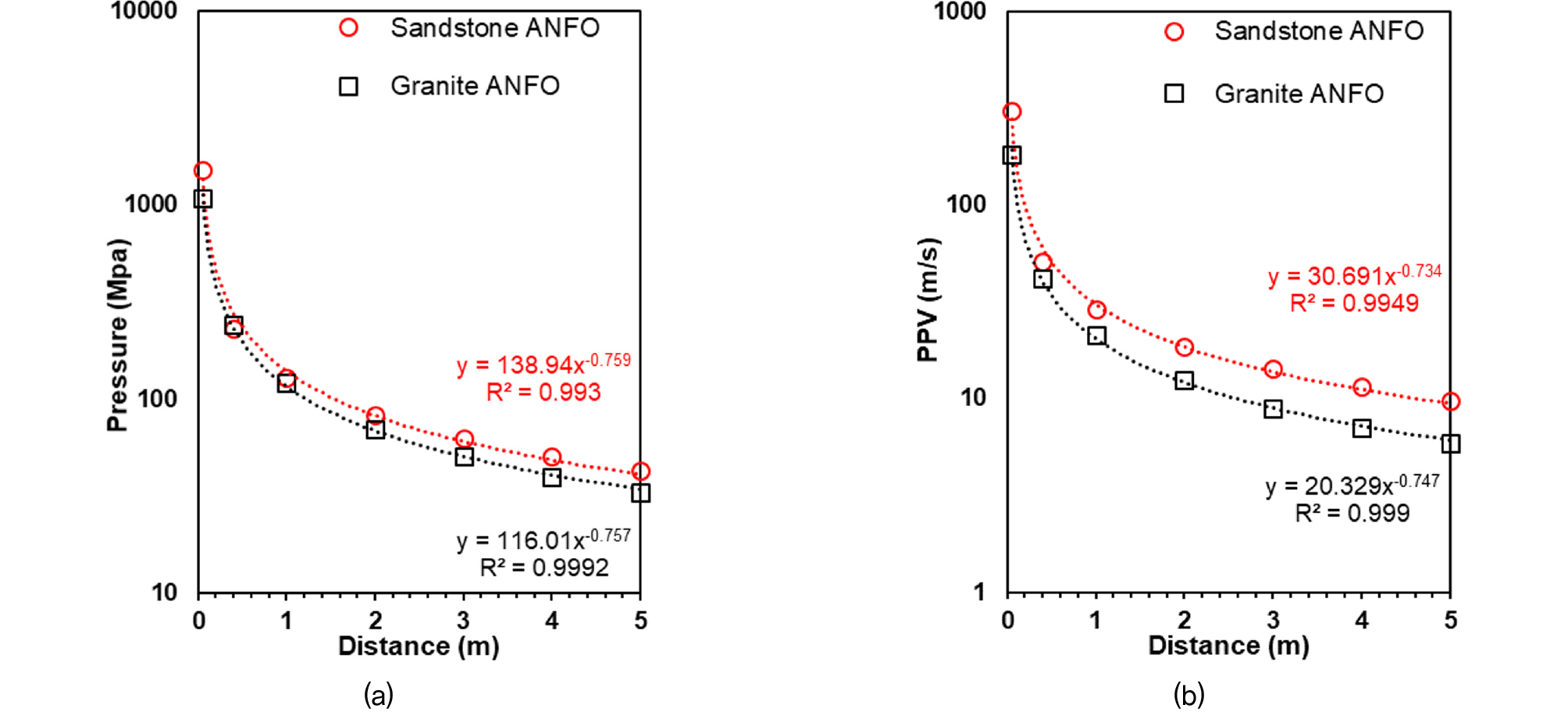

The recorded peak pressure from the borehole wall at various distances is shown in Fig. 16(a). Close to the borehole, a sharp decrease in pressure shows energy is dissipated in the crushing and fracturing of the rock. Pressure attenuates faster in granite than in sandstone. Further wave attenuates with distance and can be expressed as a power function of distance to the borehole as p = k(d)-n. Where k is the constant dependent on blast magnitude. n is the decay function. Moreover, peak particle velocity (PPV) is also obtained and shown in Fig. 16(b). PPV is extensively used in the field to assess blast-induced rock damage. Holmberg & Persson (1978) correlate PPV with distance, which can be expressed as PPV = k(d)-n. where k and n are site-specific and explosive constants. Within 1 m from the bore hole, the PPV of both rocks is above 20 m/s, which shows extensive damage to the rock and major radial fractures observed.

5. Conclusions

This research uses numerical modeling to investigate the influence of blast holes, explosives, and rock types on the prediction of fracture zone radius resulting from single-hole blasting. The fracture zone may typically be determined by theoretical models that rely on pressure and tensile strength. However, the pressure parameter is not easily available and is difficult to quantify. A large data set of Swedish experimental data has been compiled to determine fracture zones using linear charge concentration. We compare experimental data with numerically based predicted fracture zones. The medium blast holes usually utilized in tunnel blasting agree well with the upper and lower bounds of the experimental findings. We provide an equation based on linear charge concentration to determine the fracture zone. It may be used to determine the fracture zone from the charge concentration for blast design purposes. This research focuses only on coupled single-hole blasting, while decoupled blasting is often used in practice. The study will be extended to include the consideration of decoupled blasting.